When Heaven Whispered Yes

As the white smoke rises, a collective sighs: "A shepherd has been chosen". While these 44 popes may be fewer than the 266 who have worn the papal crown, each one brought something profoundly unique.

Pope Francis (2013–2025)

First Pope from the Americas, Francis embraced simplicity—living modestly in the Vatican guesthouse and driving a Ford Focus. His book, Laudato Si’, urged ecological responsibility, while his advocacy for refugees reshaped global discourse. His papacy emphasized service over grandeur to shift the Church’s focus to social justice and environmental stewardship.

Jeffrey Bruno from New York City, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Jeffrey Bruno from New York City, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Benedict XVI (2005–2013)

A theologian at heart, Benedict XVI’s papacy was marked by a focus on deepening the Church’s intellectual and theological foundations. When he resigned in 2013—unprecedented since 1415—it was a bold decision that stunned the world. Additionally, his Jesus of Nazareth series remains a significant contribution to Christian scholarship.

Elvir Tabaković, Wikimedia Commons

Elvir Tabaković, Wikimedia Commons

St John Paul II (1978–2005)

The most-traveled Pope in history (129 countries), John Paul II, was a significant player in the fall of communism, particularly in Poland. He declared 482 people saints, founded World Youth Day, and survived a 1981 assassination attempt. His leadership profoundly shaped modern Catholicism, emphasizing both faith and social justice.

Gregorini Demetrio, Wikimedia Commons

Gregorini Demetrio, Wikimedia Commons

Paul VI (1963–1978)

Implementing the Vatican II reforms, Paul VI reshaped the liturgy. Paul VI’s 1968 encyclical (a papal letter to all bishops), Humanae Vitae, upheld the Church’s stance against contraception, profoundly influencing Catholic teachings on family life. He is one of the Popes who helped modernize the Church while tackling social issues.

Fotografia Felici, Wikimedia Commons

Fotografia Felici, Wikimedia Commons

St John XXIII (1958–1963)

St John XXIII’s reputation as “Good Pope John” stemmed from his deep compassion and progressive outlook. During his reign, he initiated the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), a pivotal moment in the history of the Church. This step helped foster global dialogue of the Catholic Church with other religions.

Fotografia Felici, Wikimedia Commons

Fotografia Felici, Wikimedia Commons

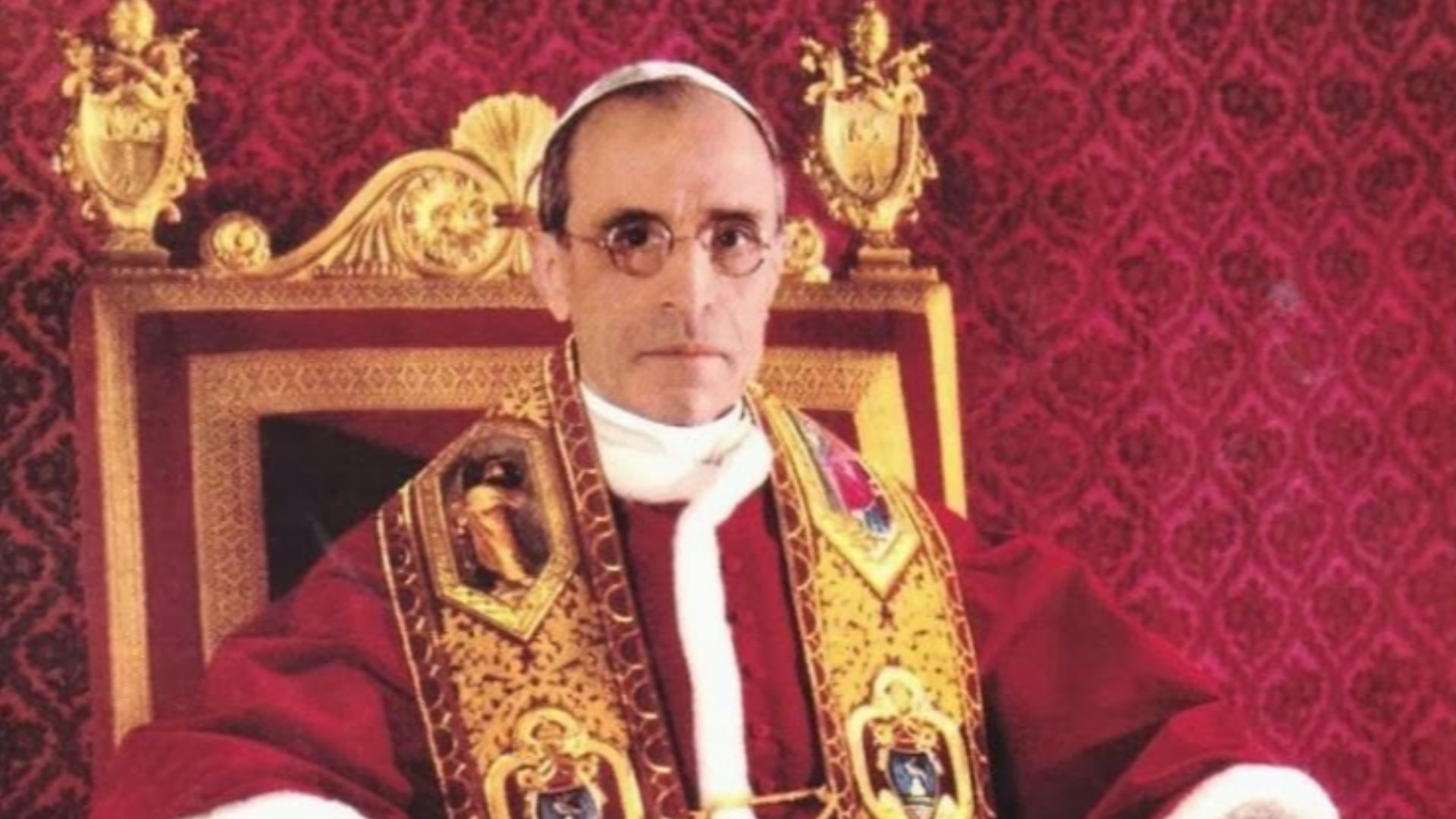

Pius XII (1939–1958)

The shadow of WWII marked Pius XII’s papacy. Despite all that, he led the Church in offering discreet aid to Jews and others suffering. He also opposed communism’s spread and advocated Christian forgiveness—even toward war criminals—in an effort to promote healing in postwar Europe.

Pius XI (1922–1939)

Pope Pius XI’s papacy was marked by the signing of the “Lateran Treaty” in 1929. This letter officially established Vatican City as an independent state. Then, in 1937, the Pope also issued the Mit brennender Sorge, which condemned Nazi violations of the Concordat and denounced the regime’s racial ideology.

Politisch Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin,1932 , Wikimedia Commons

Politisch Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin,1932 , Wikimedia Commons

Benedict XV (1914–1922)

During the chaos of WWI, Benedict XV, “The Pope of Peace,” mediated efforts to end the conflict and offered humanitarian aid to its victims. The broader global conflict often overshadowed his attempts at peace, but his actions amid such devastation left a legacy of compassion.

Giuseppe Felici, Wikimedia Commons

Giuseppe Felici, Wikimedia Commons

St Pius X (1903–1914)

The Italian Pope, St Pius X, deepened Catholic devotion through major reforms to the Breviary and the Mass. First, he restored Gregorian chant, and second, he emphasized frequent Communion, terming it “the shortest and safest way to Heaven”.

Francesco De Federic , , Wikimedia Commons

Francesco De Federic , , Wikimedia Commons

Leo XIII (1878–1903)

Leo XIII touched on the Rosary, which earned him the nickname “Rosary Pope”. His writing of Rerum Novarum in 1891 provided a moral framework for addressing the rights of workers. And as the first pope to be recorded on film, he witnessed the Vatican’s transition into the modern age.

Attributed to Enrico Canè, Wikimedia Commons

Attributed to Enrico Canè, Wikimedia Commons

Pius IX (1846–1878)

Now, here comes a Pope who has led the longest—31 years, 7 months, and 23 days, to be exact. Meet Pius IX. His doctrinal impact was profound, as he revived the Order of Pope Pius IX, now the highest papal honor, which celebrates virtue, merit, and faithful service.

George Peter Alexander Healy, Wikimedia Commons

George Peter Alexander Healy, Wikimedia Commons

Gregory XVI (1831–1846)

When Gregory XVI’s papacy ended, the world remembered his initiative in instituting the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, known as the “Gregorian Mission”. The primary objective of this mission was to convert the predominantly pagan Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Beyond his missionary work, Gregory had a record of prolific writings.

Paul Delaroche, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Delaroche, Wikimedia Commons

Pius VII (1800–1823)

Napoleon sought to strip the Pope of his temporal power, and when Pius VII refused to comply, he invaded the Papal States in 1808, seizing control by force. In retaliation, Pius VII excommunicated him, and this led to the Pope’s five-year captivity in Savona, Italy, from 1809 to 1814.

Thomas Lawrence, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Lawrence, Wikimedia Commons

Pius VI (1775–1799)

Think Pius VII was the only Napoleon captive? Nope. In 1798, he also imprisoned Pius VI with the same goal of forcing the Pope to renounce his temporal power. After being captured, Pius VI was taken to France, where he passed away eighteen months later, having reigned for 24 years.

Pompeo Batoni, Wikimedia Commons

Pompeo Batoni, Wikimedia Commons

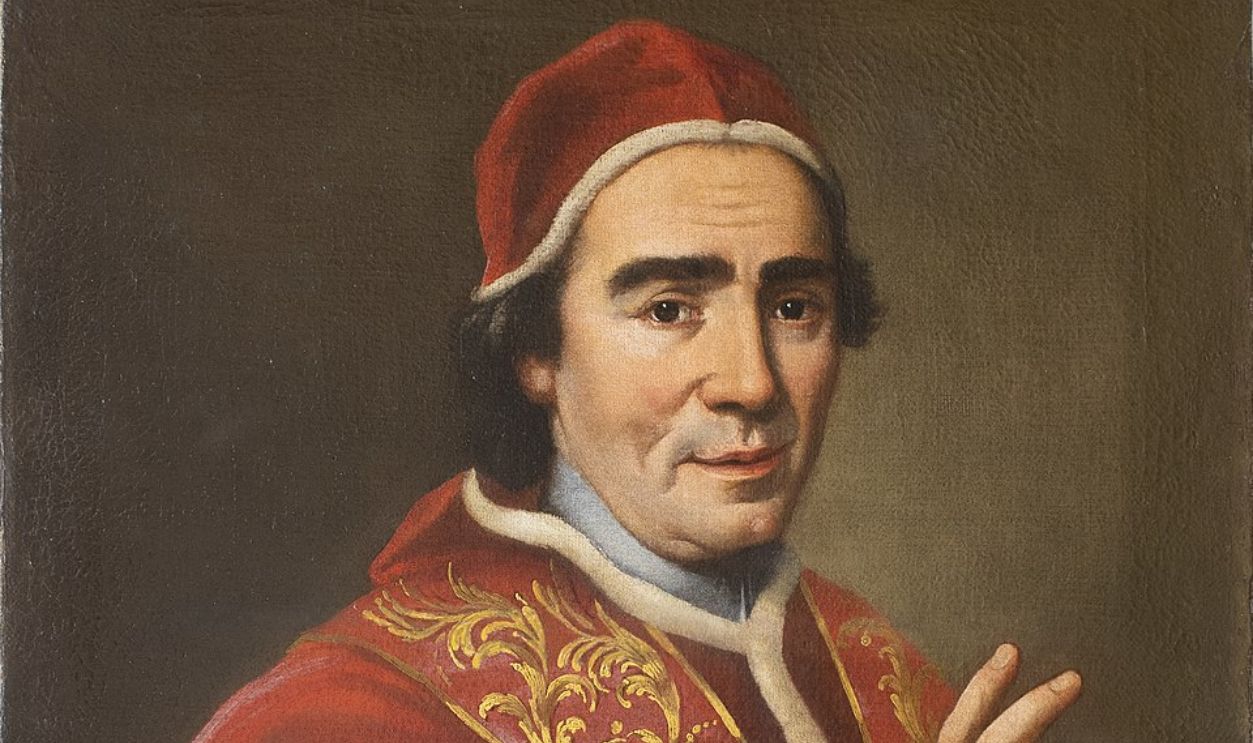

Clement XIV (1769–1774)

Clement was the certified calmer of conflict. How? The Pope suppressed the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in 1773. His decision was driven by intense pressure from European monarchs who viewed the Jesuits as politically disruptive. Though controversial, his move prevented a wider schism between the papacy and these powerful nations.

Giovanni Domenico Porta , Wikimedia Commons

Giovanni Domenico Porta , Wikimedia Commons

Benedict XIV (1740–1758)

Pope Benedict XIV was a strong advocate for scientific inquiry, particularly in medical studies. He supported dissection for anatomical research by recognizing its value in advancing both medicine and religion. The Catholic Encyclopedia even termed him “perhaps the greatest scholar among the Popes”.

Pierre Subleyras, Wikimedia Commons

Pierre Subleyras, Wikimedia Commons

Innocent XI (1676–1689)

Born Benedetto Odescalchi, Innocent XI condemned liberal moral theology in 1679 and rejected propositions on abortion and ensoulment. This step shaped the Catholic views on embryology. He also initiated the Holy League, uniting European powers to repel the 1683 Ottoman siege of Vienna.

Jacob Ferdinand Voet, Wikimedia Commons

Jacob Ferdinand Voet, Wikimedia Commons

Alexander VII (1655–1667)

This Pope took the mantle of patron of architecture and defender of orthodoxy. Alexander VII commissioned the colonnade surrounding St Peter’s Square, designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini—a visual embrace that welcomes the faithful. Even when facing challenges with European monarchs, he managed to remain a thoughtful, intelligent Pope in Rome.

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Wikimedia Commons

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Wikimedia Commons

Urban VIII (1623–1644)

Maffeo Barberini, later Pope Urban VIII, led a papacy marked by military ambition, political strategy, and cultural patronage. He expanded papal territory during the Thirty Years’s War and supported artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini. In 1631, he authorized the first-ever canonical coronation of a Marian icon.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Wikimedia Commons

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Wikimedia Commons

Sixtus V (1585–1590)

Did you know that churches sometimes accumulate debt? Well, they do, and Sixtus V saved the Church from such. With a keen focus, he reorganized the Church’s finances, rebuilt the city’s infrastructure, and improved the Vatican roads and streets to support pilgrims and tourists alike.

Pietro Facchetti, Wikimedia Commons

Pietro Facchetti, Wikimedia Commons

Gregory XIII (1572–1585)

Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian Calendar in 1582 to rectify inaccuracies in the Julian calendar, which had caused a drift in the timing of Easter. This reform adjusted leap years and skipped 10 days in October 1582 to realign the calendar with the solar year.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Pius V (1566–1572)

Tough yet tender to the faithful, Pope Pius V was instrumental in standardizing the Tridentine Mass, thereby ensuring the Catholic liturgy followed the Council of Trent. Beyond religious reforms, he united European forces under the Holy League, resulting in the decisive 1571 victory at Lepanto, which halted Ottoman expansion.

Bartolomeo Passarotti and workshop, Wikimedia Commons

Bartolomeo Passarotti and workshop, Wikimedia Commons

Paul III (1534–1549)

Paul saw what the Church had become—and acted. In the 16th century, Paul III approved the Jesuits, called the Council of Trent, and spearheaded the Counter-Reformation. Even in a corrupt climate, he earned praise for recognizing the need to cleanse and rebuild. Under his lead, Catholicism found defense and direction.

Adrian VI (1522–1523)

Adrian VI, the only Dutch Pope and the last non-Italian until John Paul II, boldly acknowledged Church corruption at the “Diet of Nuremberg”. Though his austerity measures failed to stop Lutheranism, his commitment to moral reform paved the way for the Counter-Reformation and marked a rare moment of papal self-criticism.

After Jan van Scorel, Wikimedia Commons

After Jan van Scorel, Wikimedia Commons

Julius II (1503–1513)

He didn’t just fight wars—he fought to make beauty immortal. Julius II placed the first stone of St Peter’s Basilica and commissioned Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Known for courage on and off the battlefield, people admired his vision.

Callixtus III (1455–1458)

As the defender of Europe and promoter of justice, this Spanish Pope from the Borgia family called for a crusade to defend Europe against the Ottoman Empire after the collapse of Constantinople. He also famously reopened the trial of “Joan of Arc,” posthumously declaring her innocent and a martyr.

Sano di Pietro, Wikimedia Commons

Sano di Pietro, Wikimedia Commons

Nicholas V (1447–1455)

Did you know the Vatican Library—often inaccessible to most—was part of Pope Nicholas V’s vision? He envisioned it as a hub for scholarship and the preservation of knowledge, aiming to collect thousands of manuscripts to safeguard them for future generations. Nicholas succeeded, as it has become one of history’s gems.

Peter Paul Rubens, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Paul Rubens, Wikimedia Commons

Martin V (1417–1431)

The Western Schism (1378–1417) divided Catholic allegiance, with multiple rival Popes claiming authority. The Council of Constance (1414–1418) resolved the crisis by deposing competing claimants and electing Pope Martin V, who restored unity to the Church. His papacy symbolized the return of legitimacy, and his diplomatic approach helped heal divisions.

Venetian school / After Pisanello, Wikimedia Commons

Venetian school / After Pisanello, Wikimedia Commons

Gregory XI (1370–1378)

Pope Gregory XI ended the Avignon Papacy, returning the seat to Rome in 1377 after almost 70 years in France. To arrive at his decision, he was influenced by figures like St Catherine of Siena, who urged him to restore the Church’s presence in Rome.

Workshop of Italian schools of paintings, Wikimedia Commons

Workshop of Italian schools of paintings, Wikimedia Commons

Bl Innocent V (1276)

Blessed Innocent V, the first Dominican pope, was known for his intellectual dedication to scholastic theology. As archbishop of Lyons and later cardinal bishop of Ostia, he championed Church unity at the Council of Lyons. Elected Pope in 1276, his brief five-month tenure reflected a legacy of learning and reconciliation.

Risorto Celebrano, Wikimedia Commons

Risorto Celebrano, Wikimedia Commons

Gregory IX (1227–1241)

In an age of spiritual and political upheaval, Pope Gregory IX emerged as a steadfast guardian of Church doctrine. He established the Papal Inquisition to combat heresy and codified canon law to bring unity to Church governance. Yet his compassion endured—he canonized St Francis and promoted humility and charity.

Honorius III (1216–1227)

Honorius III endorsed the Dominican and Franciscan orders, which transformed the Church’s relationship with the poor and helped anchor scholastic theology. He supported universities, particularly in Paris and Bologna, which helped establish education as a central mission of the Church during his time.

Didier Descouens, Wikimedia Commons

Didier Descouens, Wikimedia Commons

Innocent III (1198–1216)

With unmatched authority, the papacy reached its medieval peak with Innocent III. This Pope excommunicated kings, launched crusades, and presided over the Fourth Lateran Council to strengthen doctrine and promote reform. While crushing heresy and defending spiritual supremacy, he also embraced renewal by supporting Francis and Dominic.

Urban II (1088–1099)

Among the first popes to launch a crusade was Urban II. At the Council of Clermont, his call to arms for the First Crusade stirred thousands, uniting rival lords under the banner of reclaiming Jerusalem. His rallying cry gave faith a cause and altered the papacy’s political power.

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

St Gregory VII (1073–1085)

Gregory fought hard to stop kings from choosing bishops. His stand against Henry IV helped separate the Church from State power, and he proved that popes weren’t figureheads—they were spiritual leaders with real authority. His firmness made him loved by reformers and feared by emperors.

Unidentified painter, Wikimedia Commons

Unidentified painter, Wikimedia Commons

Sylvester II (999–1003)

The papacy also had highly intelligent individuals. Take, for instance, Pope Sylvester, formerly known as Gerbert of Aurillac. Sylvester was a pioneering scholar who introduced Arabic numerals to Europe. He was deeply engaged in astronomy and mathematics, challenging superstitions that saw such studies as dangerous. This bridged faith and reason.

Meister der Reichenauer Schule, Wikimedia Commons

Meister der Reichenauer Schule, Wikimedia Commons

St Nicholas I (858–867)

When St Nicholas took over, he refused to let kings rewrite marriage for convenience. He stood up to Lothair II, defended sacred vows, and reminded Europe that morality outranked royalty. To many, he was a protector of values that weren’t negotiable.

Jaroslav Cermak , Wikimedia Commons

Jaroslav Cermak , Wikimedia Commons

Zachary (741–752)

As a peacemaker and advocate for the enslaved, Zachary was a stabilizing figure during chaotic times. He brokered peace between warring Lombards and Byzantines, maintained Church independence, and denounced the slave trade—personally freeing slaves sold in Rome. Zachary’s diplomacy and compassion earned widespread respect in both East and West.

Anonymous Russian icon painter (before 1917) , Wikimedia Commons

Anonymous Russian icon painter (before 1917) , Wikimedia Commons

St Gregory I (590–604)

Also known as “Gregory the Great,” this Pope sent missionaries to England, sparking conversions that would shape Europe for centuries. Beyond that, he restructured worship and redefined leadership as service. His reforms made Christianity more organized, more global, and more accessible.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

St Silverius (536–537)

St Silverius is remembered for his unwavering commitment to orthodoxy and his courageous defiance of Empress Theodora’s demand to rehabilitate heretical bishops. The Pope chose exile and martyrdom over compromise, enduring starvation for his steadfast defense of the faith. His sacrifice under extreme persecution earned him veneration as a saint.

Artaud de Montor (1772–1849), Wikimedia Commons

Artaud de Montor (1772–1849), Wikimedia Commons

St Leo I (440–461)

Leo didn’t need swords. When Attila the Hun approached Rome, “Leo the Great” met him outside the city and convinced him to leave. No battle. Just words. He also shaped Christian doctrine at Chalcedon, clearly defining Christ’s nature. Beloved for bravery and clarity, Leo made faith feel bold and secure.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

St Sergius I (687–701)

Despite imperial pressure, Sergius I refused to condemn the Quinisext Council, resisting Justinian II’s interference in Church matters. His firm stance nearly cost him exile. He also enriched Catholic worship by introducing the Agnus Dei chant into the Mass, and this left a lasting impact on the liturgical tradition.

internet - on painter from history, Wikimedia Commons

internet - on painter from history, Wikimedia Commons

St Clement I (88–99 AD)

Clement stepped in when the Church in Corinth fell into chaos. He wrote 1 Clement—a letter so wise and balanced that some early believers treated it like Scripture. He reminded Christians that unity mattered more than ego. His voice helped preserve peace when the Church’s survival was still fragile.

St Peter (C 30–64 Or 67 AD)

Peter, who was also one of Jesus's disciples, unified Jews and Gentiles. Unfortunately, this position had him face imprisonment, beatings, and eventually crucifixion. Still, his leadership gave shape to what we now call the Church. As the first Pope, he did well. Really well.